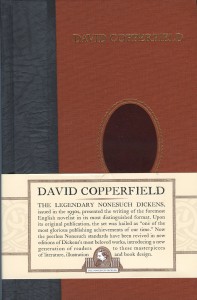

Published in 1849-1850, David Copperfield is arguably Charles Dickens’ most famous novel. I’m reading is the Nonesuch Dickens edition.

Published in 1849-1850, David Copperfield is arguably Charles Dickens’ most famous novel. I’m reading is the Nonesuch Dickens edition.

Some info on Charles Dickens, from his entry on Wikipedia:

Charles John Huffam Dickens (7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world’s most well-known fictional characters and is generally regarded as the greatest novelist of the Victorian period. During his life, his works enjoyed unprecedented popularity, and by the twentieth century he was widely seen as a literary genius by critics and scholars. His novels and short stories continue to be widely popular.

Born in Portsmouth, England, Dickens was forced to leave school to work in a factory when his father was thrown into debtors’ prison. Although he had little formal education, over his career he edited a weekly journal for 20 years, wrote 15 novels, five novellas and hundreds of short stories and non-fiction articles, lectured and performed extensively, was an indefatigable letter writer, and campaigned vigorously for children’s rights, education, and other social reforms.

Dickens sprang to fame with the 1836 serial publication of The Pickwick Papers. Within a few years he had become an international literary celebrity, famous for his humour, satire, and keen observation of character and society. His novels, most published in monthly or weekly instalments, pioneered the serial publication of narrative fiction, which became the dominant Victorian mode for novel publication. The installment format allowed Dickens to evaluate his audience’s reaction, and he often modified his plot and character development based on such feedback. For example, when his wife’s chiropodist expressed distress at the way Miss Mowcher in David Copperfield seemed to reflect her disabilities, Dickens went on to improve the character with positive features. His plots were carefully constructed, and Dickens often wove in elements from topical events into his narratives. Masses of the illiterate poor chipped in ha’pennies to have each new monthly episode read to them, opening up and inspiring a new class of readers.

Dickens was the most popular novelist of his time, and remains one of the best known and most read of English authors. His works have never gone out of print, and have been adapted continually for the screen since the invention of cinema, with at least 200 motion pictures and TV adaptations based on Dickens’s works documented. Many of his works were adapted for the stage during his own lifetime, and as early as 1913, a silent film of The Pickwick Papers was made.

My listening pleasure this month comes from Enrico Caruso, CD 4 of Enrico Caruso: The Complete Recordings.

I found this entry about Caruso fascinating,

Members of the Met’s roster of artists, including Caruso, had visited San Francisco in April 1906 for a series of performances. Following an appearance as Don Jose in Carmen at the city’s Grand Opera House, a strong jolt awakened Caruso at 5:13 on the morning of the 18th in his suite at the Palace Hotel. He found himself in the middle of the San Francisco Earthquake, which led to a series of fires that destroyed most of the city. The Met lost all the sets, costumes and musical instruments that it had brought on tour but none of the artists was harmed. Holding an autographed photo of President Theodore Roosevelt, Caruso ran from the hotel, but was composed enough to walk to the St. Francis Hotel for breakfast. Charlie Olson, the broiler cook, made the tenor bacon and eggs. Apparently the quake had no effect on Caruso’s appetite, as he cleaned his plate and tipped Olson $2.50. Caruso made an ultimately successful effort to flee the city, first by boat and then by train. He vowed never to return to San Francisco and kept his word.

In November 1906, Caruso was charged with an indecent act allegedly committed in the monkey house of New York’s Central Park Zoo. The police accused him of pinching the bottom of a married woman. Caruso claimed a monkey did the bottom-pinching. He was found guilty as charged, however, and fined 10 dollars, although suspicions linger that he may have been entrapped by the victim and the arresting officer. The leaders of New York’s opera-going high society were outraged initially by the incident, which received widespread newspaper coverage, but they soon forgot about it and continued to attend Caruso’s Met performances. Caruso’s fan base at the Met was not restricted, however, to the wealthy. Members of America’s middle classes also paid to hear him sing—or buy copies of his recordings—and he enjoyed a substantial following among New York’s 500,000 Italian immigrants.

Pinching the bottom of a married woman. And the fine was only 10 dollars. Today, Caruso likely would have been imprisoned for years and/or had has career destroyed by the media.